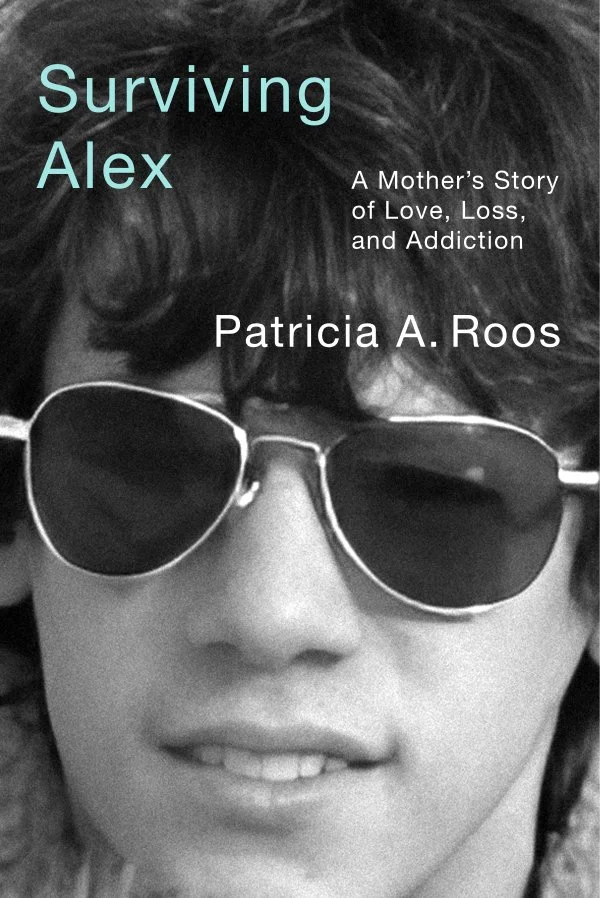

Surviving Alex

“Patricia Roos’s harrowing story of her beloved son’s struggles with mental health and addiction—intertwined with her courageous but doomed fight to save his life—dishes out near relentless heartache. But she persists, revealing the systems that failed her family and inspiring us to join her fight for desperately needed reform”

“An intensely personal and painfully honest story of the loss of a son, the cruelties of American drug and healthcare policies, and the hope that harm reduction can bring. Both a memorial and a sociological analysis, Surviving Alex shows us that addiction is indeed something to fear, but not for the reasons many of us assume.”

“Surviving Alex is a beautiful read – engaging, honest, thought-provoking, and relatable. This gripping personal story is contextualized with a thoughtful and clear-eyed characterization of the ravages of mental illness, addiction, and the drug pushers, and also offers a novel exploration of the therapeutic industry and criminal justice system.”

A Mother’s Story of Love,

Loss, and Addiction

Patricia Roos was a professor of sociology at Rutgers University when in 2015 she lost her son Alex at 25 years of age to a heroin overdose. Overnight, she shifted her research and advocacy interests, turning grief into activism. She hopes to inspire a moral community of action to address the overdose crisis. Roos spent much of her sociological career investigating systemic patterns of inequality by sex and race, focusing on how subtle mechanisms of inequity get reproduced. In Surviving Alex, she uses these skills to examine extant explanations and treatments for the ever-growing overdose epidemic and finds them wanting. Weaving together the personal and the sociological, she learns about the broader set of factors implicated in mental health and substance use disorders. Instead of focusing on individual-level choice and brain disease arguments, she directs her attention to the larger social context in which those individual-level actions occur.

Roos movingly describes the two roads families travel in the carousel ride from hell that is addiction. The ideal road—what all parents want for their child—travels a straight line through an idyllic childhood, high school and college graduations, career success, a family of one’s own. A second road—one that parents dread—heads directly into the storms, depression, anxiety, mental health disorders, substance use, and in the worst case, death. These two paths are not at opposite ends of the same continuum, but rather roads that run parallel to one other, and frequently intersect. She describes how Alex walked each of these roads, veering toward happiness, success, and sanity at some points in his life, and toward anxiety, despair, and addiction at others. She makes clear that “good families” travel both these roads, arguing that addiction happens to people from “good families.” Indeed, it can happen to anyone.

Roos skillfully integrates existing research and writing on addiction with information she gathered over the years she lived with Alex’s mental health and substance use disorders, and with the trauma associated with his death. She talked with important people in Alex’s life, including his friends, therapist, teachers, police officers, family members, and others who met him along the way. As Alex’s medical heir, she collected intake and medical information from the institutions in which he resided, providing a wealth of information from social workers, doctors, psychiatrists, rehab staff, and jailers to flesh out her personal narrative and interviews.

Ultimately, she imagines a world steeped in compassionate, paradigm-shifting harm reduction methods, as opposed to the punitive, choice-based approaches that currently exist. She champions more holistic approaches that value the humanity of those contending with substance use and mental health disorders, leading to more effective public and private policy strategies and reductions in the corrosive effects of stigma. We need to build stronger bridges from the harm reduction policy world to the lives of families facing addiction. There is substantially more to the explanation of the overdose crisis than bad choices made by those in the throes of addiction. Understanding the larger, systemic picture is key to understanding how to fix the problem, and the kinds of roles that government and private partnerships can play in developing solutions.